Do you suspect that you might be suffering from food sensitivities?

Have you been bombarded by advertisements for food sensitivity tests but aren’t sure which one to choose?

You’re not alone! There are dozens of tests to choose from, all claiming to be the best, so it’s important to do your research before you decide.

This article will differentiate food sensitivities from other types of adverse food reactions, provide an overview of common food sensitivity tests and the science behind them, and help you decide which test is best.

Want to save this article? Click here to get a PDF copy delivered to your inbox.

What Are Food Sensitivities?

A food sensitivity is a type of adverse food reaction – a term that basically encompasses all the different ways you could negatively react to a food.

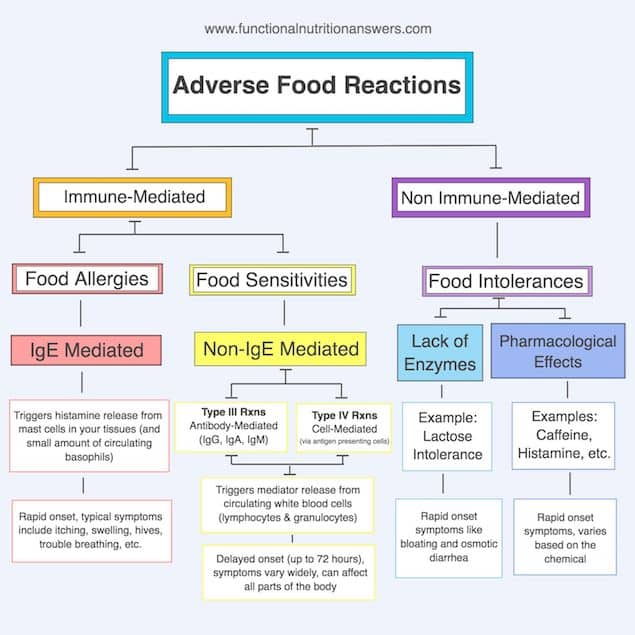

There are three main types of adverse food reactions, and each has a very different biological pathway:

1) Food intolerances: Food intolerances do not involve the immune system (1, 2). They occur when the body lacks the digestive enzymes needed to break down certain foods. An example would be lactose intolerance, in which the body cannot break down the milk sugar lactose, causing bloating and diarrhea (3). Food intolerances can also occur due to direct pharmacological effects of chemicals, like histamine.

2) Food allergies: Food allergies DO involve the immune system. They occur when the body creates IgE antibodies to a food, which then trigger the release of histamine and other pro-inflammatory mediators from mast cells (located in your tissues) next time you eat that food (4). These reactions are typically rapid, occurring within minutes or hours (1). An example would be a peanut allergy that causes swelling, hives, and difficulty breathing.

3) Food sensitivities: Food sensitivities ALSO involve the immune system, but NOT IgE antibodies (4). Instead, they occur when circulating white blood cells (lymphocytes or granulocytes) react to a food or chemical and release pro-inflammatory chemicals known as “mediators” into the bloodstream, which cause symptoms throughout the body. These reactions are often delayed and dose-dependent (5). An example would be a wheat sensitivity that causes abdominal pain, diarrhea, and brain fog the day after eating a moderate amount of wheat (6).

Unfortunately, the medical community hasn’t come to a consensus on the exact definition of “food sensitivities,” so you’ll often hear the term used in many different (and confusing) ways (2).

Some people may refer to food sensitivities as “non-IgE food allergies,” others may classify them as different types of “food intolerances,” and still others call them “delayed hypersensitivity reactions.”

While the terminology might be used differently, the science behind it is the same.

Ultimately, when we use the term “food sensitivity,” we’re talking about any immune-mediated adverse food reaction that DOESN’T involve IgE (the antibody responsible for food allergies).

The Science Behind Food Sensitivities

In order to really evaluate the different food sensitivity tests available, it is important to understand a few things about the immune system.

Any time the immune system reacts inappropriately to a harmless substance (such as food), this is called a hypersensitivity reaction (7).

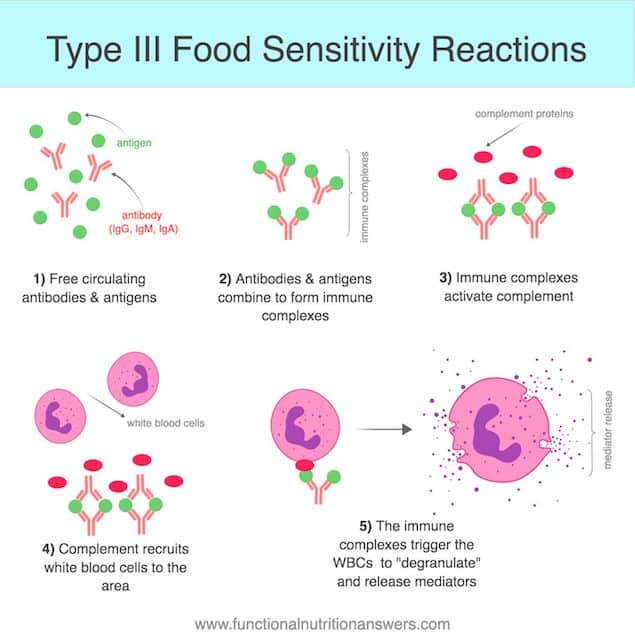

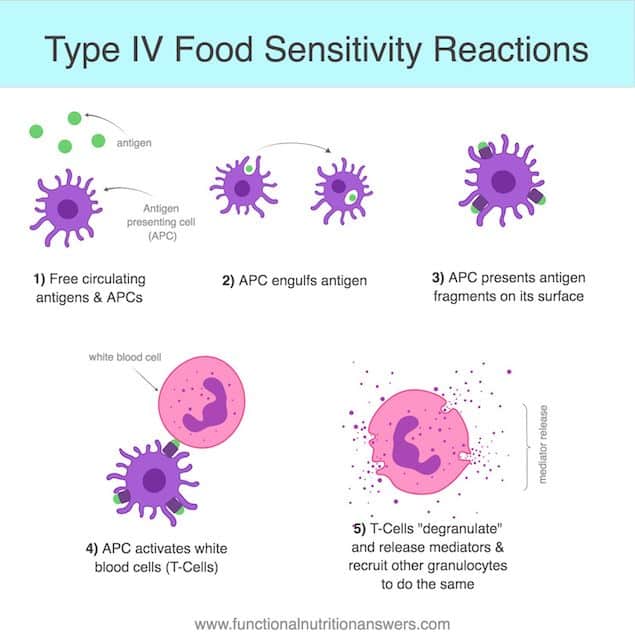

For food sensitivities (non-IgE-mediated reactions), there are two main pathways in which these reactions can occur (8):

- Type III reactions, also known as immune-complex reactions, occur when IgG, IgM, or IgA antibodies bind to a food antigen and trigger white blood cells to release mediators, which causes symptoms (7, 9).

- Type IV reactions, also known as cell-mediated reactions, occur when white blood cells (lymphocytes or granulocytes) are independently triggered to release mediators, without the involvement of antibodies (7, 10, 11).

It is important to understand that food sensitivities can be caused by both type III and type IV reactions (plus others, like cytotoxic reactions caused by chemicals, which do not neatly fit into any of these categories).

So, if you are looking for a food sensitivity test, you want one that will measure ALL types of possible pathways.

No matter which type of reaction is occurring, the end result is that mediators are released by your white blood cells (8, 12, 13).

These mediators can cause a variety of symptoms, depending on which types are released:

- Proinflammatory mediators will cause inflammation (acute or delayed) or suppress anti-inflammatory pathways (14).

- Proalgesic mediators will cause pain by amplifying the incoming pain signals to the central nervous system (15).

- Vasoactive mediators will cause blood vessels to constrict or dilate (16, 17).

- Membrane permeable mediators can cross the blood-brain barrier and have effects on the central nervous system (like increasing sensitivity to stimuli) (18, 19).

- Pyrogenic mediators will increase body temperature (20).

During a food sensitivity reaction, mediators are released by white blood cells and circulate all over the body, triggering lots of unpleasant symptoms.

This explains why someone who is suffering from a food sensitivity usually has multiple symptoms, not just one or two symptoms localized to one organ.

The best food sensitivity tests should be able to measure mediator release because that is what DIRECTLY causes your symptoms.

Who Should Get Tested?

If you feel like food may be contributing to your symptoms, but you can’t figure out which foods are to blame, food sensitivity testing might be helpful.

Unlike food allergies, which typically cause rapid symptoms, the symptoms of food sensitivities can be delayed up to 72 hours and are often dose-dependent. This can make it very difficult to pinpoint which foods are causing problems (5).

Symptoms of food sensitivities are wide-ranging and can vary quite a bit from person to person, depending on the way their body reacts and the types of mediators released.

The following is a list of symptoms that can be caused by food sensitivities (21, 22, 23):

- Fatigue

- Brain fog

- Headaches

- Mood swings

- Sinus or ear congestion

- Runny nose

- Rashes or itchy skin

- Achy joints

- Nausea

- Abdominal pain

- Bloating and gas

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Water retention

- Unexplained weight gain or loss

You may also consider getting tested if you have health conditions linked to food sensitivities and chronic inflammation, such as:

- Acne (24)

- ADHD (25, 26, 27, 28)

- Autism (29, 30)

- Chronic fatigue syndrome (31)

- Depression (32)

- Eczema (33, 34)

- Fibromyalgia (35)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (36, 37)

- Inflammatory bowel diseases (38, 39, 40, 41)

- Interstitial cystitis (42, 43)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (44, 45, 46)

- Migraines (47, 48, 49, 50, 51)

- Psoriasis (52)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (53, 54)

Of course, having any of these symptoms or conditions does not guarantee that you have food sensitivities, but typically, the more symptoms you experience, the better candidate you are for testing.

The best way to determine whether food sensitivity testing is right for you is to work with a dietitian or other licensed health care professional who specializes in adverse food reactions.

It is also worth noting that some people also choose to get tested for food allergies (via oral challenge, skin prick testing, and/or IgE blood testing) since food sensitivity testing is completely separate and cannot detect allergies.

Interestingly, while up to 35% of people report adverse reactions to certain foods, only 3.5% of them are actually due to true allergies. It is estimated that 50 to 90% of adverse food reactions are actually due to sensitivities or intolerances (56).

What Types of Tests Are Available?

There are many food sensitivity tests to choose from, but some are better than others.

Let’s review 11 of the most common food sensitivity tests and evaluate the science behind them.

1. Mediator Release Testing (MRT) + LEAP Diet

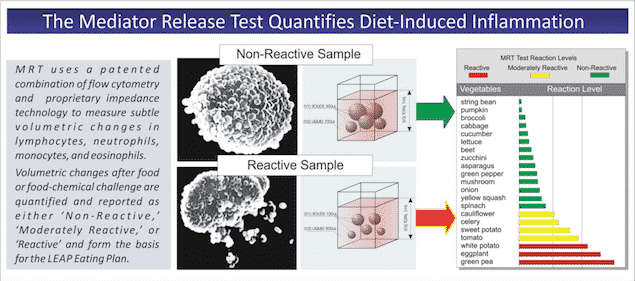

Mediator Release Testing (MRT) was invented by immunologist Mark Pasula as a way to identify food sensitivities.

How does it work?

MRT is a blood test that can be ordered through a healthcare professional or directly from Oxford Biomedical Technologies (in the US/North America) or ISO-LAB (in Europe).

To perform the test, the client gets their blood drawn and shipped overnight to a lab. (The overnight shipping is important to ensure that the blood cells are still alive for testing.)

Once received, the blood sample is divided up and mixed individually with the 141 food antigens and 29 chemicals that are tested on the MRT panel.

A machine then monitors to see how much the white blood cells shrink in size after exposure to these antigens.

The more the cells shrink, the more pro-inflammatory mediators they have released, and the stronger the food sensitivity reaction is (57, 58).

Say what?

Let’s break down the physiology.

At rest, when white blood cells haven’t reacted to anything, they are storage houses for various types of mediators.

That means when no reaction has occurred, your blood has a relatively stable solid-to-liquid ratio. (Solid cells filled with mediators, floating around in the liquid portion of your blood.)

However, when these white blood cells are exposed to an antigen, they respond by releasing some of their mediators into the surrounding environment, which causes them to shrink in size.

This then CHANGES the solid to liquid ratio of your blood.

The more mediators your white blood cells release, the smaller they get, and the more the solid-to-liquid ratio decreases.

This is a totally normal process that occurs constantly as our immune system evaluates its environment (this process is commonly referred to as the “oral tolerance” process).

A moderate amount of mediator release is a normal part of the oral tolerance process.

In a healthy functioning immune system, this minor inflammatory reaction is counterbalanced by the release of anti-inflammatory mediators to neutralize the reaction (59).

However, if the immune system detects something that it deems a threat, it will go hog-wild and release A LOT of pro-inflammatory mediators, causing a much larger than “normal” reaction.

This abnormal change in the solid-to-liquid ratio is then flagged on the MRT test results as either “moderately reactive” or “highly reactive,” depending on the size of the response.

How are these changes actually measured?

MRT uses two types of technologies (flow cytometry and impedance technology) to measure changes in the solid-to-liquid ratio of the blood.

In regular people terms, this means that the blood passes through a fancy machine that uses lasers and electrical currents to determine the volume of solid particles within the blood (60).

Since each person is unique, they serve as their own control for the test. Only changes in the solid-to-liquid ratio that are several standard deviations from “normal” for that individual are flagged as reactive.

One of the strengths of the MRT test is that you can actually see the magnitude of each response on the test results, as indicated by the length of each bar:

(Image used with permission from Oxford Biomedical.)

This is really helpful when trying to decide which foods to include at which stages of an elimination diet.

Another positive of the MRT test is that they use high-quality “lyophilized antigens” (which basically means freeze dried) that have not been denatured or otherwise changed by harsh extraction methods (61).

The goal is to use antigens that are as close as possible to what the immune system would encounter in the gut if those foods were eaten.

Finally, another unique benefit of MRT is that they not only test food antigens but also chemicals like caffeine and amines that naturally occur in foods.

This gives dietitians the ability to customize their patient’s diet to avoid foods that contain these triggering substances.

MRT can detect both type III and type IV food sensitivity reactions.

This is probably one of the most important concepts to wrap your head around in regards to food sensitivity testing.

MRT measures the amount of mediators released from your white blood cells.

Mediators are what cause food sensitivity symptoms, so they are the MOST IMPORTANT thing to measure.

We don’t really care which pathways triggered their release.

It could have involved antibodies, like IgG, or the white blood cells could have been triggered directly without the involvement of antibodies.

Again, it doesn’t really matter.

What we ultimately want to know is DID mediators get released in response to a certain food or chemical. THAT is the clinically relevant information.

The importance of working with a Certified LEAP Therapist (CLT)

MRT can be ordered directly from Oxford Biomedical Technologies, but it is HIGHLY recommended that you work with a Certified LEAP Therapist (CLT) for the best results.

CLTs are registered dietitians who have passed the CLT certification offered by the creators of the MRT test.

CLTs have been educated on the physiology of food sensitivities, trained on how to interpret MRT test results, and taught how to implement a customized elimination diet known as LEAP.

LEAP stands for “Lifestyle Eating and Performance,” and refers to the elimination diet that is used along with your MRT results.

The LEAP protocol usually lasts 6 to 8 weeks, becoming progressively less restrictive as new foods are introduced.

For the first 2 weeks, you eat roughly 25 of your lowest reactive foods (preferably ones you already eat on a somewhat regular basis so your immune system is familiar with them) in order to calm diet-related inflammation and allow for symptoms to subside.

Then, once you are actually feeling better, you can begin to add foods back in, one at a time, from least reactive to more highly reactive, watching for any reactions that may occur.

This is done under the supervision of a “Certified LEAP Therapist” (CLT) who has been trained to interpret MRT results and help patients complete the LEAP protocol.

It is important to note that the foods labeled as “reactive” on your MRT results should NOT be blanket-statement avoided forever. It is important to work with your dietitian to eventually add them back into your diet and test your tolerance.

It IS possible (although not guaranteed) to regain oral tolerance to some foods, and unnecessary restriction should always be avoided.

It is also incredibly important to understand that testing can give you a starting point for doing a customized elimination diet, but it is NOT the end-all-be-all.

Food sensitivity testing does NOT test for allergies, intolerances, or other types of possible adverse reactions that can occur, such as intestinal allergy (allergies that only manifest in the gut) or histamine intolerance.

Because of this, you should always let your body be the guide, and listen to its responses above all.

To find a CLT near you, go to HealthProfs.com, type in your zip code, filter the search results for “Nutritionists and Registered Dietitians” and then click “Certified LEAP Therapist” under “Treatment Techniques” on the left-hand side.

Many CLTs work remotely (via phone or video chat), so it is worth expanding your search if there are no CLTs in your immediate area.

Is there evidence to support this test?

While there is a large amount of research to support the involvement of food sensitivity reactions in chronic inflammatory conditions, there is very little research on food sensitivity tests themselves.

As of November 2018, no peer-reviewed research studies have been published on MRT or the LEAP elimination diet. However, preparations are underway for a future study on the effectiveness of LEAP for IBS-D.

While no studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals, a small amount of data has been published or presented elsewhere:

-

- LEAP reduces IBS symptoms: A clinical presentation given at the 2004 annual meeting for the American College of Gastroenterology showed that the LEAP diet (guided by MRT results) decreased IBS symptoms by 53% in one month (62).

- LEAP reduces circulating cytokines: A follow-up study on a single subject with IBS-D showed an increase in circulating cytokine levels during an IBS-flare and lower levels of cytokines when symptoms were in remission (62).

- IBS patients have more circulating cytokines: To follow up the single-subject experiment, cytokines in the blood were compared for a group of normal healthy adults and those with IBS. IBS patients had significantly higher levels of many types of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to controls (62).

- MRT has 94% sensitivity and up to 91% specificity: A study published by the Polish Pediatric Association found that MRT detected food sensitivity reactions to at least one cow’s milk protein in 94% of milk-allergic children who displayed symptoms after an oral challenge and had a 16% false-positive rate in healthy adults with no symptoms (63). A second data set showed that 91% of the tested items were negative for healthy asymptomatic adults (64).

- Greater than 90% split-sample reproducibility: Oxford Biomedical is a CLIA accredited lab which must pass quality control measures biannually. MRT advertises a greater than 90% split sample reproducibility, but only provides one example to back up these claims (65).

While high-quality research is still lacking, this doesn’t mean that the test isn’t “evidence-based” (66).

According to an article published in the Journal of The American Dietetic Association (now the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics), “evidence-based practice uses the best available evidence, the results of peer-reviewed scientific studies, whenever possible, and, when the science is lacking, expert opinion and experience” (67).

In this case, the research to support this specific testing method is lacking, but the physiology behind it and the theory of why it works is solid.

Food sensitivity reactions that cause systemic inflammation are a REAL thing and have been well studied and published on for decades.

It is also well established that many chronic illnesses have an inflammatory root, in which food often plays a role.

MRT helps connect these dots by determining which foods are contributing to the inflammatory load.

These foods can then be temporarily removed during the LEAP protocol to reduce inflammation while oral tolerance is restored.

Although testimonials are not enough evidence alone to support a test or protocol, it is worth noting that thousands of practitioners use MRT and LEAP with great results (68).

The Verdict: MRT is generally considered to be the best food sensitivity test available since it can detect mediator release caused by BOTH type lll and type IV hypersensitivity pathways. However, peer-reviewed research is needed for both MRT and the LEAP protocol.

2. Antigen Leukocyte Antibody Test (ALCAT)

Similar to MRT, the aim of ALCAT is to measure the amount of mediators released by white blood cells in response to different food antigens.

It was actually developed in the 80’s by Dr. Pasula (the same guy who created MRT), but Dr. Pasula eventually separated from that company and created MRT using newer technology for more accurate results.

How does it work?

ALCAT works much in the same way as MRT. The client orders the test through a healthcare provider or directly from Cell Science Systems (North America only), gets their blood drawn locally, and mails the sample overnight to the lab.

Like MRT, the patient’s blood sample is exposed to a variety of antigens and monitored for changes in cell sizes.

However, ALCAT uses an older impedance technology, which is not quite as accurate as the more modern (but patented) three-dimensional ribbon impedance methods used by MRT (69).

Additionally, the way ALCAT presents its results is different than MRT.

Rather than being presented as a bar graph (which indicates the magnitude of the immune response), ALCAT results are grouped into 4 broad categories:

- Acceptable Foods

- Mild Intolerance

- Moderate Intolerance

- Severe Intolerance

However, as we know, there can be a wide range of reaction-sizes, even within the “low-reactive” or “acceptable” categories.

It is very helpful to know which foods provoke the least amount of inflammation when designing an oligoantigenic elimination diet.

Since ALCAT doesn’t quantify the degree of reactivity within each category, there’s no way to know exactly how much inflammation is caused by any given food.

Additionally, the dietary therapies recommended by ALCAT and MRT differ as well.

MRT promotes a customized oligoantigenic diet (LEAP) based on a person’s test results, whereas ALCAT promotes a rotation diet with all “acceptable” foods, followed by the eventual reintroduction of reactive foods to test for tolerance (70).

The LEAP diet is more restrictive in the initial phases, but also more highly customized, and thus more likely to produce rapid symptom relief.

However, there are still a few benefits of ALCAT.

One benefit of ALCAT is that it tests for a wider variety of antigens (357 on ALCAT vs 170 on MRT), including foods, herbs, food additives, medications, and even molds.

However, a larger testing panel also introduces more opportunity for error, false-negatives, and false-positives that may hinder someone’s attempt at an elimination diet.

However, ALCAT does not test for as many naturally occurring chemicals (like caffeine or amines) as MRT.

Like MRT, ALCAT also uses freeze-dried antigens to mimic what the immune system would see when the food is consumed.

ALCAT is able to detect both type III and type IV food sensitivity reactions, so it is still more clinically useful than IgG testing (71).

Is there evidence to support this test?

There is a combination of peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed data to support ALCAT:

Non-Peer-Reviewed:

- ALCAT can distinguish between people with food sensitivities and healthy controls: Data presented at a 1988 immunology conference found that healthy young adults had significantly fewer positive results on the ALCAT test vs people with suspected food sensitivities (2% vs 20% positive results) (72).

- ALCAT + avoidance diet can improve symptoms of migraine, eczema, and rhinitis. Data presented another conference in 1988 showed that 77% of migraine sufferers, 71% of eczema patients, and 100% of rhinitis patients experienced symptom relief after removing foods that were “reactive” on the ALCAT test. Only 50% of IBS patients improved, likely because roughly ⅓ of them actually had yeast overgrowth, not IBS (73).

- ALCAT has 79% sensitivity and 87% specificity for foods: Data presented at a 1996 conference showed that 79% of foods marked as “reactive” on ALCAT provoked symptoms during an oral challenge, while 87% of foods not reactive on the test did not cause oral challenge symptoms (74).

- ALCAT has 95% sensitivity and 92% specificity for food additives: Again, data presented at a conference found that 95% of food preservatives and colorings that tested positive on ALCAT also elicited symptoms in a double-blind placebo-controlled test and 92% of the non-reactive additives did not elicit any symptoms (75).

Peer-Reviewed:

- An ALCAT-based elimination diet can improve IBS symptoms: In a 2017 double-blind randomized controlled trial, IBS patients experienced greater global improvement and significantly reduced symptom severity after a 4-week ALCAT-based elimination diet compared to a sham diet. No differences in quality of life measures were seen between groups, and there was a clear (but less significant) placebo effect from the sham diet. Mean symptom score improvement was better than that seen with low-FODMAP diets (76).

- ALCAT can identify non-celiac gluten sensitivity just as well as a blinded food challenge: ALCAT and a blinded gluten challenge both correctly identified 64% of people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity (77).

- ALCAT can identify foods that induce DNA release from white blood cells: 70% of foods that tested reactive on an ALCAT test have been shown to elicit a greater release of DNA from white blood cells (which then kicks off an immune response). This lends support to the theory behind ALCAT (and MRT) (78).

- ALCAT has 72% sensitivity and 82% specificity: In a different set of data published in The Journal of Nutritional Medicine, 72% of the foods that tested positive on an ALCAT test elicited IBS symptoms, while 18% of foods that did not test reactive also produced symptoms (79).

- An avoidance diet based on ALCAT results improves IBS symptoms: In the same study, 2/3rds of the IBS patients experienced significant symptom relief within 2 weeks of eliminating foods that were reactive on ALCAT (79).

The Verdict: ALCAT is considered the second-best option behind MRT. It also measures mediator release from white blood cells, but uses slightly different technology, presents the results in a different manner, and recommends a less specific diet-therapy than LEAP. However, it does have more published research than MRT at this time.

3. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) Testing

IgG testing is probably the most popular and well-known type of test for food sensitivities. Sadly, its clinical utility doesn’t measure up to its popularity.

How does it work?

Like the previous tests, clients have a blood sample taken and then mail their blood to a lab.

The blood sample is then mixed with a variety of food antigens, and the levels of IgG antibodies are measured via ELISA or RAST.

If elevated levels of IgG antibodies for a particular food are detected, then the results will show that you are “sensitive” to it.

However, a large body of research has found that the presence of IgG antibodies alone does NOT indicate a food sensitivity (80).

In fact, some studies have suggested IgG may be a marker of food tolerance rather than a food sensitivity (80, 81, 82).

The truth is, IgG production is a normal part of the oral tolerance process.

Most companies (like Pinnertest, EverlyWell, Cyrex, and Genova Diagnostics) test total IgG or IgG4 levels. However, there are a few labs that measure other components as well:

- IgG, IgG4, IgE, + Complement (Dunwoody Labs): This lab can test for both allergies (IgE) and sensitivities. By testing both IgG4 and total IgG, it can better discriminate between protective and pathogenic responses (83). A moderate amount of IgG4 can be protective, whereas large amounts can drive inflammation. Additionally, if complement is produced, a reaction may be more severe (84).

- IgG + Complement (KMBO): Similar to Dunwoody, KMBO measures IgG and complement, but it does not measure IgG4 or IgE.

- IgG + IgE (Meridian Valley Lab): This test checks for both IgG AND IgE antibodies, but the results don’t specify which one was produced in response to which foods. Instead, both types of antibodies are all lumped together, so there’s no way of knowing whether you might have an allergy, a sensitivity, both, or neither.

- IgG + IgA (Alletess): Looking at both IgG and IgA antibodies is slightly more comprehensive than IgG alone but still misses type IV reactions.

Is there evidence to support this test?

Testing of IgG levels is accurate, but the problem is that it is just not clinically useful (85, 86).

- In some cases, IgG may be protective against adverse food reactions.

- The presence of IgG does not always = an inflammatory response.

- There is no clear correlation between IgG levels and symptoms.

Sure, some of the foods that test positive on an IgG test MAY, in fact, be triggering food sensitivity reactions.

Therefore, eliminating all of them may help people feel better if they were able to get rid of some of their biggest dietary triggers.

This may explain why some studies HAVE seen improvements in IBS and migraine symptoms after eliminating foods that tested positive on IgG tests (87, 88, 89).

However, a person may NOT feel better after eliminating “reactive” foods on their IgG test if their worst food sensitivity reactions are NOT caused by IgG antibodies.

Remember, there are multiple pathways that can cause food sensitivity reactions, and IgG is just one. IgG testing cannot detect type IV hypersensitivity reactions.

Additionally, there is a big chance of over-restricting the diet based on IgG test results alone, so it is important to eventually reintroduce reactive foods back into the diet and monitor the body’s response.

IgG testing has been well researched, and many associations have released statements that it should NOT be used for the detection of food sensitivities.

These include the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (90, 91, 92).

The Verdict: Overall, IgG tests are appealing because they are quick and relatively cheap, but they are not good indicators for food sensitivities. IgG production is a normal part of the oral tolerance process, and may actually indicate exposure or tolerance to a food. IgG testing does not measure mediator release (which is what actually causes symptoms) and cannot detect type IV hypersensitivity reactions.

4. LRA by ELISA/ACT (Advanced Cell Test)

LRA was developed by Dr. Russell Jaffe in 1984 as a way to detect food sensitivities. It stands for “Lymphocyte Response Assay.”

How does it work?

Like the previously mentioned tests, the client orders this test through a health care provider or directly from ELISA/ACT Biotechnologies, takes a blood sample, and mails it overnight to the lab.

Up to 504 antigens can be tested, including foods, additives, molds, dander, medications, and herbs.

Unfortunately, the details of exactly how this test is performed are very vague on the ELISA/ACT website.

Based on the information provided in this peer-reviewed study, we determined the following:

Once the sample is received, the blood is then centrifuged to isolate the lymphocytes and plasma.

This mixture is placed inside wells that contain an antigen bound to their surface and incubated for 3 hours.

The samples are then evaluated by hand using a light microscope.

Five different fields of view are examined per well, and the results are averaged. (This leaves a lot more room for error than other tests that use automated calibrated machines.)

A reaction is flagged and considered “moderate” if 25 to 50% of the lymphocytes in the well “show activation” or considered “strong” if more than 50% of the cells “show activation.”

“Show activation” is defined as a symmetrical increase in the volume of the glycocalyx (the outer layer surrounding the cell).

Asymmetrical increases in volume are considered to be “false positives” and are ignored.

The assumption is that this increase in volume is caused by the activation of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) of the white blood cell, which triggers an immune response.

However, there is no research provided to support this assumption.

These results are then compiled in a document and sent to the practitioner or patient. Clients are advised to avoid strongly reactive items for 6 months and moderately reactive items for 3 months before trying again.

Is there evidence to support this test?

One of the most worrisome parts about this test is the lack of transparency about their testing methodology and the major scientific inaccuracies on their website.

For example, this table comparing and contrasting LRA to MRT, ALCAT, and IgG testing incorrectly classifies the different reaction types and misunderstands entirely what MRT & ALCAT measure.

Another weakness of this test is that LRA proclaims to analyze lymphocytes, but that leaves out an entire other class of white blood cells, known as granulocytes, that can also participate in food sensitivity reactions.

The makers of the test claim that it has less than a 0.1% false-positive rate and less than 1% false negative rate (93).

However, there is no public data available to support these claims and there have been no published studies regarding the reliability or validity of LRA.

One peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain showed an improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms after removing foods that tested positive on LRA, but the study was not blinded or randomized and is horribly confounded by the use of supplements and clinical support groups in the treatment protocol (94).

The Verdict: LRA is not a good choice for food sensitivity testing. Its testing methodology is not clearly explained, and it only examines one type of white blood cell (lymphocytes), leaving out an entire class of food sensitivity reactions that involve granulocytes. There is no high-quality research of any kind to support the use of this test.

5. Cytotoxic Testing

Cytotoxic testing (also known as Bryan’s test) has been around since 1947 as a way to identify food sensitivities (95).

How does it work?

A blood sample is taken and centrifuged (spun around in a machine) to separate the white blood cells.

The cells are mixed with plasma and water and placed on glass slides that have various dried food antigens on them.

The slides are then examined under a microscope after 2 hours to look for changes in the size, shape, or number of the cells.

The idea is that a large number of shrunken, dead, or damaged cells indicates a food sensitivity to that antigen.

Is there evidence to support this test?

Unfortunately, since this test is done by hand, there is a lot of room for error and it is not considered to be very accurate or reliable.

Additionally, since the practitioner is only looking at the cells on a two-dimensional slide, there is no way to tell for sure whether the cells just changed shape or if they actually shrunk in size.

There are also many other factors that could affect the size/shape/activity of white blood cells, including the pH, temperature, incubation time, and possible contaminants on the slides that are not well controlled for with this method (96).

A study done in the 70’s found that 73% of the results were reproducible in 5 out of 6 tests done on the same person, but that the results didn’t correlate well with the person’s self-reported symptoms (97).

However, this is not surprising since food sensitivities are often delayed and dose-dependent and can’t typically be identified just by asking someone which foods they think they react to.

Cytotoxic testing has been deemed “ineffective and without scientific basis” for the detection of allergies (but no mention of sensitivities) by the FDA and the American Academy of Allergy (98, 99).

The Verdict: Given the large potential for error with cytotoxic testing, it is rarely used anymore and is not recommended for the detection of food sensitivities.

6. Live Blood Analysis (LBA) by Darkfield Microscopy

Live blood analysis (also known as live cell analysis, nutritional blood analysis, or Hemaview) is a test sometimes used by alternative medicine practitioners and chiropractors to diagnose food allergies or sensitivities (100).

How does it work?

The test is performed at a practitioners office, where a drop of blood from a finger prick is placed on a microscope slide under a glass coverslip.

The blood is then viewed using a “dark-field microscope,” which shines light from underneath the slide, rather than above.

This creates a dark background and bright cells in the foreground, which can be displayed on a television monitor for easier viewing.

According to Live Blood Online, a company that offers training in this method, the practitioner then examines the blood for “abnormalities” in the size, shape, ratio, or structure of red and white blood cells, platelets, and more.

However, it is unclear how any of these abnormalities would relate specifically to food sensitivities, or how you would obtain any information about what you are sensitive to.

The Weston A. Price Foundation published a small (non-peer reviewed) study in its own newsletter, suggesting that live blood analysis may be a valuable tool for evaluating blood clotting patterns and that people with higher inflammation levels may have faster rates of clotting (101).

While it is true that inflammation is linked to blood clotting, it is unclear how live blood analysis would help someone understand whether food was playing a role in their inflammation levels or which foods might be problematic for them (102).

Is there evidence to support this test?

While this technique IS considered a valid scientific tool for examining blood cells and detecting certain types of bacteria in the blood, to date, there is no research to suggest it should be used for the evaluation of food sensitivities (103, 104).

As of 2001, no live blood cell analysis provider had been able to meet the requirements of CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendments of 1988) and live blood analysis remained classified as an unestablished laboratory test (105, 106).

The Verdict: Live blood analysis can be a useful tool in some situations, but NOT for food sensitivity testing. There is no research to support its use for this purpose, and it is unclear how it would be helpful.

7. Electrodermal Test (Vega)

The Vega test (also known as electrodermal testing) was invented in the 1970’s as a way to diagnose food allergies or sensitivities (107).

How does it work?

Electrodermal testing uses a type of “electroacupuncture,” in which an electric current is passed through the body using two pieces of equipment, usually a hand-held probe and a second smaller probe placed on acupuncture points by the practitioner.

A “Vega machine” is then connected to the same circuit and a test substance (like a heavy metal) is placed inside the machine.

If the machine shows a drop in the reading when exposed to this “toxic” substance, the machine is considered properly calibrated.

The practitioner then repeats this process, placing a variety of foods in the machine one by one, watching for changes in the electrical readings (skin impedance) after exposure.

The idea is that when the body is exposed to a food or other substance it does not tolerate, it triggers an autonomic (subconscious) nervous system response that changes the way electricity is conducted through the skin (107).

Since the Vega machine is monitoring how quickly electricity passes between the two probes, it can pick up on these small changes.

Based on the results, the practitioner will provide a list of reactive foods or substances to avoid.

Is there evidence to support this test?

While it is possible to measure changes in skin impedance with the Vega machine, it is unclear how those changes might relate to food sensitivities, specifically.

Published data has only focused on IgE allergies and is wildly inconsistent, ranging from no correlation with skin prick results to a 90% correlation (107, 108, 109, 110).

However, since these studies involved allergies, not sensitivities, it is unclear whether electrodermal testing might be helpful for other types of hypersensitivity reactions.

Issues that make electrodermal testing less reliable include possible user error (applying the electrodes with the right pressure) and the potential for over-testing in one area (107).

It also cannot be used on anyone with a pacemaker and can be affected by things like battery-powered watches, fluorescent lighting, or a high electromagnetic field in the area (107).

The Verdict: While electrodermal testing has its proponents, it is unclear how changes in skin impedance would indicate food sensitivities, and there have been no studies done to evaluate its effectiveness for this purpose.

8. Hair Testing

Recently, a few companies have been advertising hair testing as a method for detecting food allergies, sensitivities, and intolerances.

How does it work?

The client collects a sample of their hair and mails it to the company.

The sample is then “analyzed” and the customer receives a report showing their food and environmental sensitivities.

Is there evidence to support this test?

There is no validated method of testing sensitivities or intolerances through hair.

Several hair testing labs report that they use “bioresonance” machines to test hair for food sensitivities (111, 112, 113).

These machines are designed to detect an individual’s “morphogenetic field encryption pattern” – a pattern of energy that can supposedly be measured in any cell of an object (114).

The idea is that certain foods or substances disrupt this energy pattern, which can trigger the immune system & contribute to chronic illness.

Some practitioners then recommend “bioresonance therapy” to “rebalance” the energy fields and correct a variety of illnesses.

However, studies on this topic have been low-quality and with mixed results (115, 116, 117, 118, 119).

While this is an interesting theory, at this time, there is no science to support the existence of morphogenetic fields, and no data to link it to food sensitivities, allergies, or intolerances (120, 121).

The Verdict: While hair testing may be useful for other purposes, such as the detection of heavy metals, there is no research to support its use for food sensitivity testing.

9. Coca Pulse Test

Pulse testing for food allergies and sensitivities was first described by Dr. Arthur F. Coca in 1956 (122).

How was it developed?

Dr. Coca’s wife began experiencing unexplained chest pain one day, and she noticed that her attacks were the worst within minutes after eating certain foods. He tested her pulse after she ate these foods and found that it was faster than usual.

So, they began tracking everything she ate and testing her pulse before and after eating each food. She removed the foods that seemed to elevate her pulse, and she found that her chest pain was gone.

He began practicing this technique on many of his patients and claimed to have “almost miraculous” results.

Is there evidence to support this test?

Unfortunately, there’s not much research to back up these claims.

It is true that some types of food sensitivity reactions can trigger the release of mediators that affect heart rate, so the mechanism is plausible.

But, since food sensitivities are dose-dependent and often delayed, pulse-testing would not be a very reliable method unless the food triggered a very clear and rapid response.

It is also important to note that pulse rate can be affected by many other factors, including your own emotions or thoughts about the food.

A small study from 1961 got mixed results with pulse testing and questioned its usefulness in clinical practice (123).

The Verdict: The mechanism behind the Coca pulse test is plausible, however, pulse rate can be affected by so many other factors and food sensitivity reactions are not always immediate, so it is probably not a very reliable way to test for sensitivities.

10. Applied Kinesiology (Muscle Testing)

The use of applied kinesiology, or muscle testing, to assess food sensitivities is gaining popularity and is practiced by nearly 40% of chiropractors (124).

How does it work?

This test is performed in an office by practitioners trained in this method.

There are various ways to perform the test using different muscles of the body, but the most common uses an extended arm (testing the deltoid muscle in the shoulder).

To do the test, the patient is asked to hold a vial of a substance in one hand (or place a substance under the tongue) and hold the other arm out to the side, parallel to the floor.

They are asked to keep their arm in place, without pushing upwards, while the practitioner pushes down on the arm from above.

If the arm holds strong and does not move, the body is considered to be tolerant of the food or substance the person is holding at the time.

If, however, the limb weakens and moves when force is applied, it is believed that the body does not tolerate that food.

This test can be repeated using a variety of vials containing different substances.

The belief behind this testing is that the body has energy pathways (called “meridians” in Traditional Chinese Medicine) that can be affected by food or other environmental triggers.

When these energy pathways are disrupted, the body is “weakened,” as detected by muscle testing.

The practitioner will then recommend avoiding the foods or substances that weaken the body in order to improve health.

Proponents of this testing method highlight that it is non-invasive and easy to perform, with immediate results.

Is there evidence to support this test?

There is currently no peer-reviewed evidence to support the use of muscle testing for the detection of food sensitivities.

Since it is administered by a person, there is large room for error, and interpretation can vary based on the training and experience of the practitioner.

Studies have attempted to validate its use for detecting true IgE allergies or reactions to known poisons, but have not had positive results:

- Muscle testing cannot accurately detect allergies: One study found that muscle testing was unable to detect true IgE allergies to wasp venom and only had a 3% overall test-retest reliability, between and within practitioners (125).

- Muscle testing results did not differ significantly from chance: A second study tested the same items twice, in a blinded manner, and only got the same results 33% of the time (126).

- Muscle testing correctly detected vials of poison only 53% of the time: A study comparing saline solution to a toxic hydroxylamine chloride solution found that muscle testing was only able to detect the toxic vials 53% of the time (127).

While scientific evidence is lacking for muscle testing, there are many anecdotal reports of its usefulness and it is still widely used to this day.

Many who use it consider it to be just one tool in the toolbox, but not diagnostic of anything. Results should always be verified with labs when possible.

The Verdict: There is no research to support the usefulness of applied kinesiology for detecting food sensitivities. Most published research has found that it is not much better than chance at identifying problematic foods or substances.

11. Elimination Diets + Food Challenges

The gold standard for diagnosing adverse food reactions is called a “double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge” (DBPCFC) (128).

While it is the most well-controlled and accurate method, it is also very time-consuming to do for multiple foods.

Because of this, DBPCFCs are most commonly used to test whether people are truly allergic to foods that have come back positive on a skin prick test, but that the person has never eaten.

This means that DBPCFCs are more commonly used in the context of IgE-mediated allergies, rather than delayed hypersensitivities, but they still can be used for this purpose.

How does it work?

A double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge is just what it sounds like.

It is double-blinded, meaning that neither the patient nor the practitioner knows which foods are being consumed when. This is so that their perceptions do not influence the results.

It is also placebo-controlled, meaning that the patient separately introduces the suspected problem food and a placebo substance (without knowing which one is which).

Before introducing either of these substances, the patient is put on a strict diet for a few days that only contains a few foods that are (presumed to be) well-tolerated.

This is done in order to wash out any reactions that might have been lingering from previous exposure, as well as to control the diet so the only thing that changes is the exposure to the test substances.

Then, under the supervision of a doctor, one set of capsules containing either a food antigen or a placebo is added to the diet in increasing dosages and the patient and physician document any reactions that occur. This is then repeated with the other set of capsules.

Symptom records are evaluated to determine whether an adverse reaction occurred or not. Only then is it revealed which capsules contained the food antigen, and which ones contained the placebo.

This method is helpful because you are only challenging one food at a time in a very controlled manner, so you can be relatively sure that any differences in symptoms are due to the food.

However, it isn’t very practical for most people, especially when you aren’t sure which food or foods might be causing your symptoms.

When conducted in the context of allergies, which typically have rapid-onset symptoms, a DBPCFC can be performed in a few hours at a doctor’s office (with an epi-pen on hand, just in case).

However, when conducted for delayed hypersensitivity reactions, it is more likely to be done at home over a longer time period, typically around 1 week.

Because DBPCFCs are relatively difficult to perform, they are not typically very helpful for detecting food sensitivities, especially if someone has no idea which food or foods might be the culprit.

For food sensitivities, elimination diets are more commonly used.

To conduct an elimination diet, a person “eliminates” a large variety of potentially problematic foods and only consumes a restricted diet until symptoms subside (usually a few weeks to 1 month)

Once the person feels significantly better, eliminated foods are systematically reintroduced to test for tolerance.

Some commonly used elimination or semi-elimination diets include Whole30, Autoimmune Paleo (AIP), and even low-FODMAP.

The most commonly eliminated foods include dairy, gluten, grains, legumes, nightshades, lectins, and/or highly-fermentable carbohydrates.

However, there is no guarantee that any of these foods are at the root of your symptoms.

It is quite possible to have hypersensitivity reactions to foods that are commonly considered “healthy,” like salmon, kale, quinoa, or turmeric.

Without guidance on which foods are actually triggering immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, blanket elimination diets can only get you so far.

You might get lucky and determine a few of your biggest symptom-triggers, but then again, you might not.

The Verdict: Double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges are considered the “gold standard” in identifying adverse food reactions but are very difficult and time consuming to do. There are a wide variety of elimination diets that can be used to identify problematic foods, but they are less personalized than elimination diets created based on food sensitivity testing results.

How Much Does Food Sensitivity Testing Cost?

Most food sensitivity tests cost several hundred dollars to perform, plus the cost of working with a dietitian or other practitioner that specializes in adverse food reactions.

However, it is important to remember that cheaper is not always better when it comes to lab work.

The majority of the low-cost options only measure IgG levels and cannot detect the other types of food sensitivity reactions (cell-mediated, type IV).

It is worth spending more money for a more clinically useful result.

Additionally, your appointments with a dietitian or other licensed healthcare practitioner are often covered or reimbursed by insurance, which can help lower the cost.

Which Test Is Best?

MRT and ALCAT are the only tests that measure the release of mediators, which are ultimately responsible for food sensitivity symptoms.

MRT, however, uses updated technology and the LEAP protocol to more accurately pinpoint which foods are causing problems, so it is generally considered to be the best.

This doesn’t mean that other tests can’t provide some potentially useful information, but MRT (paired with LEAP) will give you the most actionable results and best therapeutic diet.

Although no peer-reviewed studies have been published yet to confirm the validity of MRT, its methods are backed by science, and many people have experienced significant symptom relief after following the LEAP diet protocol.

Where Does Testing Fit in My Wellness Plan?

It is important to note that ALL medical tests are simply sources of information, but how you USE that information is what really matters.

Food sensitivity testing results should never be interpreted as a list of foods to avoid forever.

Rather, they should be used to craft a customized diet that will quickly reduce inflammation, followed by a period of diet expansion and symptom monitoring.

In the context of functional nutrition, testing for and addressing food sensitivities would fit into the “Remove” section of the 5-R protocol (Remove, Replace, Repopulate, Repair, Rebalance).

The idea is to identify and remove any foods that are contributing to systemic inflammation or causing other types of adverse reactions. Testing can often help streamline this process.

Again, it is important to recognize that food sensitivities are often the tip of the iceberg. They rarely occur in a vacuum.

Working with a functional-minded practitioner can help you address the root causes of your symptoms and help you achieve optimal health and wellness.

Want to save this article? Click here to get a PDF copy delivered to your inbox.

Disclosures: Both Erica and Amy are Certified LEAP Therapists. However, they have no financial relationship with Oxford Biomedical and are in no way compensated for recommending MRT to patients or peers. Similarly, Amy and Erica do not have any financial ties to any of the other companies mentioned above.

This article was a joint-venture, written by both Erica Julson, MS, RDN, CLT (owner/founder) and Amy Richter, MS, RDN, LD, CLT (lead writer). Erica and Amy are experienced registered dietitians who are passionate about creating great nutrition content!

thank you so MUCH for this extremely detailed and thoughtful article. there must have been a heart of gold behind it to be so thorough for the benefit of others.

Which one of these tests is the Vibrant Zoomer test?

Thank you for this thorough post and an answer for those who think food sensitivity tests are a Hoax.

The real question.. Is there an accurate test for gut allergies like histamine intolerance?? I just did the MRT and noticed alot of the foods that are non-reactive for me cause histamine issues… So i’m pretty disappointed as this test is extremely expensive.

I got mixed results too. I’m celiac yet wheat and barley didn’t show as reactive. Some foods I questioned did while others did not. Very disappointed in the results. I got no closer to finding out which foods make me sick with this test.

Before I give you some clarity I want to make it very clear and stated that I have no connection nor any benefits to promote the MRT test and get any kickbacks by answering any questions.

My name is Dr ND ,BCNS,HHLP-FDN-P board-certified functional medicine doctor etc.

I have been using this particular test for the past 14 years I have spoken with The top science department like Ethan… and just like you in the beginning I had so many doubts and uncertainties…

I have ran on myself – then probably over 3000 testing through the years as I can run food sensitivity test with GENOVA Cyrex BioTek you get the point…

I don’t know when the last time you have done the test but there’s been some changes that occur through showing you a number next to your score and even though the type of food all toxic could be in the green if the number is pretty high it should be considered as reactive…

Since most lab will only test for IgG immediate respond and the good ones will add IgG4 and even IgA.

Remember this is not a IgE test …

Since I don’t know anything about you I don’t know any thing about your Health history this is all an assumption which I literally disliked but at the same time I understand your frustration and because you have to get certified to interpreted this test compared to other labs there’s a good reason for that…

It’s extremely easy to even Google foods that are high in histamines or foods that are high in lectins or inflammatory foods like night shades …

Gluten for example which will show as wheat Or dairy the types of food can show all greens but if you know for example if you have the HLA Gene than you are more prone for gut issues Lyme – and you’re lacking of the DAO enzyme which helps our body to break histamines something that you can find out extremely easy.

Please read this few times and i’m pretty sure something will click—-

IgG testing often indicates exposure to foods rather than pathogenic reaction. Furthermore, there are 3 things that an elevated level of IgG to food could mean:

1. Pathogenic – Type 3 hypersensitivity – mechanism involved in triggering mediator release – but it’s the mediators that make you sick, not the IgG.

2. Protective – could prevent mediator release

3. Normal – neither protective nor pathogenic, just produced as a normal consequence of food consumption.

If IgG is pathogenic, it means it is causing mediator release. So theoretically MRT should identify all the IgG reactive foods. Does it? My guess is that it covers most if not all of them. I couldn’t say with certainty that it covers all of them since actual studies have not been done to prove it.

But, no test anywhere is ever totally accurate or infallible. It is possible that an IgG test, assuming it was accurate, would pick up something missed by MRT. But remember that an elevation could be pathogenic, protective or normal. So, it is possible none of the high IgG foods were actually bad for someone. Thus, when running IgG, one would need to leave all high foods out for 3 months, then add back in one at a time, eating the food 3X per day for 3 days, looking for a reaction in order to ID the pathogenic IgG response food(s), if any.

There have been over 200 studies on IgG vs. food with 2 important conclusions. Number 1 is that elevated levels of food specific IgG do not correlate with inflammation. Number 2 is that elevated levels of food specific IgG do not correlate with symptoms. The reason is because the limited role IgG can play in inflammation and symptom production are not a function of how much is produced to a specific food. It is typically a function of the internal environment within the body, where certain factors, such as the formation of too many smaller immune complexes, or deposit of immune complexes in various parts of the body, activate complement leading to elevated inflammation and/or tissue damage. But how much specific IgG is produced provides zero insight into these other critical factors. IgG has less clinical utility than guessing. Not so with MRT, which is a functional quantification of sensitivity pathways to specific foods. MRT has much higher clinical utility and provides the best information regarding the likeliest safe foods for each client.

FACT’S

1. Food sensitivities change over time, due to many factors (frequency of exposure, oral tolerance mechanisms, stress, etc.). So it should be expected for you to see variances in testing over time. Even within one week, IgG results can change 18%, and it is the longest term antibody! If your test was from US Biotek, nearly every result will show a reaction to cow’s milk/dairy, wheat/gluten, and eggs. I have had several reports of such results from physicians that tested MANY patients and those items came back reactive nearly all the time. Another set of results I observed from 2 completely different patients were the same, and cow’s milk, gluten, and eggs were reactive. 2. Same lab reliability with IgG testing has come a long way over the past 10-15 years, but interlab IgG testing is still very poor. What that means is US Biotek has excellent split sample reproducibility. So does Immunolabs. So does Genova/Metametrix. But if you sent the same sample to all 3 labs, there would be considerable variance. But that’s not even the real issue. The question everyone should ask of every test intended to identify sensitive foods is “what is the test actually measuring, and how does that relate to the inflammatory process?” In other words, what is the function of IgG (or any antibody or cellular reaction) in causing inflammation and thus symptoms. Because if IgG IS pathogenic, then the only way it produces symptoms is through an inflammatory response (white cells releasing mediators). So how does it do that, if it does it at all? An inflammatory response caused by foods means that through whatever pathway/mechanism, that reaction ends up causing mediator release. It is the release of cytokines, leukotreines, prostaglandins, etc. from various white cells that leads to the manifestation of negative effects including symptoms. No mediator release, no inflammatory reaction, no symptoms because of it. Period. This is true whether it is food allergy, food sensitivity or celiac disease. I can tell you exactly how MRT relates to this process. I can also tell you how IgG is inflammatory and under what conditions. I can also tell you, because of my understanding cultivated over 20 years focusing on these very topics is that IgG to foods is seldom clinically useful. I am not trying to offend anyone here, but you can get better results from guessing. Just take out wheat and dairy and in the vast vast majority of cases that will produce virtually the same clinical results as avoiding ALL IgG reactive foods. There may be anecdotal reports of other food triggers identified by IgG, but the 2 conclusions of medical authorities after review of over 200 studies on IgG vs. food who accept other types of antibody tests in adverse food reactions (IgE and celiac testing), is that it does not correlate with inflammation and because of that it does not correlate with symptoms. Therefore it has very poor clinical utility. In fact, in successful allergy immunotherapy 3 things happen: 1. Inflammatory symptoms decrease, 2. Allergen-specific IgE decreases, and 3. Allergen specific IgG INCREASES! Again, we have to understand what is the FUNCTION of IgG to foods and how it might cause inflammation. I cannot tell for sure you how LRA by ELISA-ACT is involved in the inflammatory process and exactly how comprehensive it is as far as being able to account for different pathways (although I have a pretty good idea) because nowhere apart from their own marketing literature does it say anything about lymphocyte transformation (the observable halo they see on their test) as a marker for allergic disease. My best guess is that it probably does a good job with Type 4 hypersensitivity, as that is T-cell mediated. But IF it is able to distinguish reactive antibodies from non-reactive antibodies, how does it do that? And how can it identify reactive and non-reactive antibodies, but not be able to account for IgE mediated reactions, when that is the classic scenario of “reactive” antibody, especially when t-cells make the determination that a particular antigen qualifies as an allergen? And if they are only looking at T-cell reactivity, then innate immune reactions are totally out of the question as these are not governed by t-cells. T-cell reactions are an adaptive immune response, not innate immunity. When these situations are properly understood, everyone will be able to make much better decisions about which tests offer the greatest value and how to utilize that information to help design diets that will produce the maximum benefits to our clients in the shortest period of time.

I hope this give you some sense of caring

And hopefully understanding.

You can call The lab and tell them name –

Dr Sagi Kalev – To assure you that beside being a loyal customer and supporter of course I do not benefit by any mean by defending them or speaking in any terms to benefit myself or the lab.

Blessing’s-Lt Dr kalev

This is extremely helpful. One thing that I am wondering about all these tests is whether they will identify a food to which you are sensitive if you haven’t eaten it for a while? I remember my doctor at some point saying there is no point in testing for wheat sensitivity if you haven’t been eating it. Is that true?

Hi Sarah, This physician isn’t correct. With MRT, people frequently come back reactive to foods they’ve not consumed in a long time, but know/suspect they have issues with. Our innate immune system at work. Now, if testing for celiac, you must be consuming wheat for accurate results, but the MRT is not a test for gluten sensitivity or celiac disease.

Hi Jane, besides tTg antibody for testing CD, and since MRT is not a good test for gluten sensitivity, which test would be suitable to for non celiac gluten sensitivity? or is an elimination diet the way to go?

This article is comprehensive and shares a good review of these different test methods. I will share that although I am in agreement with most of your points, I have used the LRA tests in my practice for years. I have found them to be very useful and helpful.

What an interesting article, thanks so much for all this information! I’m interested in this because I just ordered a food intolerance test. Can’t wait to see what it comes back with!

Are you familiar with VibrantWellness Zoomer tests? Are they reliable?

Thank you for the information, this was very precise and makes my decision to go with the clinical method of detection even firmer. Though, do you have an opinion on breadth tests like food marble? Do you think those are any better or worst? Thanks for your response.

It is a very advantageous post for me. I’ve enjoyed reading the post. It is very supportive and useful post. I would like to visit the post once more its valuable content. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for sharing. Food Sensitivity Testing is done to analyze the effects of various foods on our body. This type of testings gives unique results about different foods and their causes.

Excellent article, just what I was looking for. Thank you!

Good compilation.

There is one aspect concerning the blood cell-based assays that might be worth mentioning. The vast majority of white blood cells are neutrophilic granulocytes. These are covered with receptors for antibodies, immunecomplexes and they react strongly to a components of activated complement. Thereby mixing plasma, cells and allergens can result in a IgG antibody-dependent cell activation, which can result in swelling of the neutrophils, they may even burst, and release of granula. Both effects result in cell size and shape.

The limitation is that none of these cell tests are really quantitative, none of the mentioned is acctually measuring the release of mediators. Minor contamination of the allergen extracts, e.g. with dead bacteria, may result in false-positives.

With IgG ELISAs you may get a quantitative result, but will measure a lot of antibodies without pathogenic relevance. But the ELISA tests for IgE allergies are facing very similar issues.

So far there is a lack of good science on the topic, but there are some interesting recent findings on IgG4 and eosinophilic esophagitis. Have a look on this on pubmed.gov.

Thank you for explaining…the ELISA/ACT LRAa thought seemed the best..now.. what would be the test worth taking.? Thank you kindly.

This article is SO helpful Erica and Amy. This research would have taken me forever. Thank you!

Wow! What a comprehensive article! Food sensitivity is such a complex issue and all the tests out there can be confusing. Thanks for sharing this valuable information!

Wow this is very informative! Thanks!

This is an amazing reference, great job and thanks for sharing with the world!

Such a wealth of great information here Erica! I just learned a LOT and am looking forward to using this as a resource in the future.

holy moly this is thorough and so well researched! Thank you for writing such a comprehensive article!!

this is a great comprehensive article. thanks for sharing the information!