SIBO stands for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth – a condition in which bacteria overgrow within the small intestine, where they normally don’t exist in large numbers.

When bacteria overpopulate the small intestine, they ferment carbohydrates from the food we eat, causing uncomfortable symptoms.

Because the symptoms of SIBO are so general (abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation, bloating), it can be difficult to correctly diagnose without using tests.

The most common way to test for SIBO is through breath testing, but there are several different types.

This article will explain the science behind testing for SIBO, the pros and cons of each method, and which test is best.

Want to save this article? Click here to get a PDF copy delivered to your inbox.

Clickable Table of Contents

What is SIBO?

Typically, we think of having a lot of gut bacteria as a good thing, and it usually is!

The right balance of gut bacteria provides a long list of benefits – it aids in digestion, nutrient production, and immunity, to name a few (1).

But sometimes there are TOO MANY bacteria hanging out in places they don’t belong, like the small intestine. This is called small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, or SIBO.

In a healthy gut, bacteria are prevented from entering and thriving in the small intestine through several defense mechanisms (2, 3):

- Hydrochloric acid in the stomach kills bacteria that we’ve ingested.

- Pancreatic enzymes and bile destroy bacteria that have survived the stomach.

- The cells that line the small intestine (and probiotics) release antimicrobial peptides that fight infection.

- Intestinal mucus traps bacteria while intestinal contractions (peristalsis) transport them out of the small intestine.

- Immune cells attack pathogenic bacteria.

- The ileocecal valve (between the small intestine and colon) prevents colonic bacteria from moving backward into the small intestine.

SIBO occurs when one or more of these defense mechanisms fail, and bacteria begin to colonize the small intestine in large numbers.

When bacteria are in the small intestine, they digest carbohydrates from our food, producing large amounts of gas that can cause VERY unpleasant symptoms.

Symptoms can vary, but these are some of the most common (2, 3):

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- Belching

- Bloating (often extreme)

- Brain fog

- Depression and anxiety

- Diarrhea, constipation, or both

- Fat malabsorption

- Fatigue

- Flatulence

- Food sensitivities or intolerances

- Gastroparesis

- Heartburn

- Nausea

- Nutrient deficiencies

- Weight loss

Unfortunately, SIBO can’t be diagnosed by symptoms alone, because the symptoms are too general.

Instead, diagnostic tests should be used to rule in or rule out SIBO.

Who Should Be Tested for SIBO?

Anyone who has persistent unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms like bloating, gas, and diarrhea and has not had success with medical or dietary interventions should consider being tested for SIBO.

The best candidates for testing are those who, in addition to displaying the symptoms listed previously, have one or more of the following conditions linked with SIBO (2, 4).

- Autonomic neuropathy in diabetes (5)

- Celiac disease (6, 7)

- Chronic kidney disease (8)

- Chronic pancreatitis (9)

- Crohn’s disease (10, 11)

- Cystic fibrosis (12)

- Deep vein thrombosis (13)

- Diverticulitis (14)

- Fibromyalgia (15)

- Gallbladder removal (16)

- Gallstones (17)

- H. pylori infection (18)

- Hypothyroidism (19)

- Immunodeficiency syndromes (like IgA deficiency, AIDS, etc.) (20, 21)

- Interstitial cystitis (22)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (23)

- Liver cirrhosis (24, 25)

- Multiple sclerosis (26)

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (27)

- Obesity (28, 29)

- Parkinson’s disease (30, 31)

- Radiation enteropathy (32, 33)

- Restless leg syndrome (34)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (35)

- Rosacea (36)

- Scleroderma (37, 38)

- Short bowel syndrome (39, 40)

Of course, SIBO is not present in everyone who has one of these conditions, and we still don’t know whether it is a cause, consequence, or unrelated co-occurring phenomenon.

Since testing can be expensive out of pocket, some practitioners choose to treat suspected SIBO with antibiotics (prescription or herbal), based on symptoms alone.

Ultimately, it’s up to the practitioner to screen patients and determine who might benefit most from SIBO testing.

What Types of SIBO Tests Are Available?

To diagnose SIBO, we have to be able to measure whether there are large amounts of bacteria present in the small intestine.

Currently, this can be done either by performing a small intestine aspirate and culture or breath testing.

1. Small Intestine Aspirate and Culture

A “small intestine aspirate and culture” is considered the gold standard for diagnosing SIBO (2, 4).

A sample of fluid from the small intestine (usually the duodenum or jejunum) is collected using a flexible tube called an endoscope (41).

To get a more reliable result, samples are taken from multiple sites throughout the small intestine, because the bacteria can vary depending on the location (4).

The samples are then taken to a microbiology lab where they can be cultured and the bacteria can be quantified.

For a diagnosis of SIBO, there must be greater than 100,000 CFU (colony-forming units) per milliliter of sample fluid (although some researchers prefer a much lower cut-off of 1,000 CFU per mL) (4, 42).

Unfortunately, experts disagree about the validity of using these cultures to diagnose SIBO because they have several issues that may interfere with the results (43).

For example, samples can be contaminated by bacteria from the mouth or stomach as the endoscope passes through the GI tract (42).

In addition, some species of bacteria found in the small intestine can’t actually be grown outside the gut on a culture medium, so the results may be falsely low or skewed (44).

Despite these issues, small intestine aspiration and culture is still considered the gold standard for SIBO diagnosis.

However, it isn’t commonly used in clinical settings because it is a very expensive and invasive procedure. Instead, most practitioners prefer to use non-invasive breath tests.

2. SIBO Breath Testing

Breath testing is based on the fact that gut bacteria produce gases when they ferment carbohydrates.

The main gas produced is hydrogen (H2), but some gut microbes can convert hydrogen into methane (CH4), an odorless gas, or hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which smells like rotten eggs (45, 46).

About 80% of gases formed in the gut are expelled when we pass gas. The other 20% diffuse into the bloodstream and travel to the lungs, where they are exhaled and can be measured in our breath (2).

Any hydrogen, methane, or hydrogen sulfide gas found in the breath can be assumed to be a product of bacterial or archaeal fermentation because there are no other sources of these gases in the human body (45).

Breath levels of these gases serve as INDIRECT measurements of gut microbes because they only estimate the number of bacteria based on the amount of gas produced. They do not measure bacteria levels directly (47).

Some tests only measure hydrogen, but it’s better to measure BOTH hydrogen and methane since hydrogen can be converted into methane by archaea in the gut (42, 48, 49).

It would be ideal to measure hydrogen sulfide levels as well, but as of early 2019, no tests are commercially available (50).

In general, methane-dominant SIBO is linked to constipation, while hydrogen and hydrogen sulfide-dominant SIBO are linked to diarrhea.

Understanding which type of bacteria (methane, hydrogen, and/or hydrogen-sulfide producing) are colonizing the small intestine can guide treatment recommendations since different antimicrobials are better at eradicating each type.

For diagnosing SIBO, breath tests are recommended because they are non-invasive, inexpensive, and simple to perform (42, 45).

How does SIBO breath testing work?

During a breath test, you will be asked to first provide a breath sample to establish your baseline breath hydrogen levels.

Then, you will consume a liquid carbohydrate substrate (either glucose, lactulose, or both) and continue to provide breath samples every 15-20 minutes for 2-3 hours (42).

The breath samples are later sent to a lab where the gases can be measured and interpreted.

Is breath testing reliable?

Of course, there are some issues that may limit the usefulness of breath testing.

The biggest problem with breath testing is that it’s not standardized, so results may differ based on how the test was performed and interpreted by your provider (47).

New data also suggests that breath testing does not correlate well with the supposed “gold standard” jejunal aspirate testing (51).

Despite these issues, breath testing is still the best clinical tool available for diagnosing SIBO at the moment (42).

Which SIBO Breath Test is Best?

All breath tests measure hydrogen (and sometimes methane), but different carbohydrate substrates can be used in the testing beverage.

The two main carbohydrates used are glucose and lactulose (47).

Other substrates, like fructose, lactose, and sorbitol are available but used to diagnose carbohydrate malabsorption, not SIBO (47).

1. Glucose Breath Test

How does it work?

Glucose is a monosaccharide (the simplest form of carbohydrate) that is primarily absorbed in the proximal (first section) of the small intestine (4).

This means that glucose typically does not reach the colon where bacteria are, and thus, does not lead to the production of hydrogen or methane gas.

However, in someone with SIBO, there are bacteria within the small intestine (where they really shouldn’t be in) that WILL ferment the glucose and produce gas (52).

Thus, if breath hydrogen or methane levels increase significantly after consuming glucose, then SIBO is likely present (47).

Pros of glucose breath testing:

The main benefit of using glucose is that it is less likely to produce false positive results (47, 53, 54).

Since glucose is usually completely absorbed in the small intestine, it is less likely that fermentation from bacteria in the colon will interfere with results (47).

If a large increase in gas production occurs during the testing period, you can be fairly confident that there is SIBO.

Cons of glucose breath testing:

However, there is a potential downside to using glucose.

Since glucose is rapidly absorbed in the small intestine, it may not be able to identify SIBO that occurs in the distal (last section) of the small intestine (47, 54).

People with this type of overgrowth may show false-negative results on a glucose breath test because the sugar never reaches the bacteria for fermentation.

While this is the general consensus amongst most healthcare practitioners, new data suggests that glucose actually can reach the colon in some people.

One study traced the path of glucose through the intestines while simultaneously doing a breath test, and found that it WAS able to reach the colon and be fermented by colonic bacteria in 13% of the study population (55).

These participants had glucose breath tests that looked positive for SIBO, but were actually indicative of normal colonic fermentation.

Because of these findings, some researchers argue that glucose breath tests may be better indicators of glucose malabsorption than actual SIBO (51).

Additionally, there is some evidence from animal studies that diet may impact how well the gut absorbs glucose. Those who consume a lot of glucose are better able to absorb it than those who eat low-carb, which could also impact results (56, 57, 58).

Still, glucose is preferred by many experts (4, 59, 60).

Overall, the diagnostic accuracy of the glucose breath test is estimated to be around 72% (4).

2. Lactulose Breath Test

How does it work?

Lactulose is a disaccharide (consisting of fructose and galactose) that is poorly absorbed by the intestines (47).

When consumed by healthy individuals, lactulose makes its way to the large intestine, where it is metabolized by colonic bacteria and hydrogen and methane gases are produced (4).

In those with SIBO, however, the large number of bacteria in the small intestine begin to metabolize lactulose before it reaches the large intestine, causing an early increase in gas production (47).

Any remaining lactulose then travels to the large intestine, where it is metabolized by colonic bacteria, causing a second increase in gas production (47).

Pros of lactulose breath testing:

The benefit of using lactulose is that it travels through the entire small intestine, so you can get a better idea of what’s happening in the ileum (the final section of the small intestine), where SIBO sometimes occurs (61).

Cons of lactulose breath testing:

The downside to using lactulose is that it’s especially prone to false positive results (47, 54).

If intestinal transit time (the time it takes for food to move through the intestines) is faster than average, lactulose might reach the colon too soon.

When this happens, the gas production that occurs looks very similar to a SIBO positive test result.

Those who experience frequent diarrhea typically have a faster transit time, so lactulose breath tests aren’t as reliable for these patients (47).

Also, lactulose itself has been shown to reduce transit time and has been used as a laxative (62, 63).

Additionally, concerns have been raised about the reproducibility of lactulose test results.

One study found no significant correlation between test results conducted on the same people just two weeks apart (64).

Overall, the diagnostic accuracy of the lactulose breath test is estimated to be around 55% (4).

3. Doing Both Breath Tests

Since both glucose and lactulose breath tests have limitations, some practitioners choose to do both tests in order to aid in making a diagnosis.

Labs that offer both glucose and lactulose testing kits typically offer a discount when purchased together.

Pros of Glucose + Lactulose Breath Testing:

By using both substrates, it may be easier to detect SIBO located at either end of the small intestine, potentially reducing the likelihood of false-negative test results.

Cons of Glucose + Lactulose Breath Testing:

Ordering both tests is more expensive than using a single-substrate test and is not guaranteed to provide more clarity.

Most practitioners prefer one test over the other (usually glucose) and only order a single substrate test kit.

Where to Get Tested

Physicians’ orders are required to obtain a lactulose breath test, but glucose breath tests can be ordered directly, without a physician.

Laboratories like QuinTron and Aerodiagnostics offer glucose or lactulose breath testing, while BioHealth offers dual glucose and lactulose kits.

Make sure that whatever testing company you choose reports BOTH hydrogen and methane levels for the most accurate results.

How to Interpret Test Results

Unfortunately, there are no universally accepted standards for interpreting SIBO breath tests (4, 42, 47).

Interpretation can be difficult, so we’ve provided a few examples of what positive and negative test results may look like for both glucose and lactulose breath tests.

It’s important to note that these are just examples and results can vary quite a bit, so it’s best to follow interpretation guidelines and consult with experienced practitioners.

General Guidelines for Interpretation

The first step in interpreting a breath test is to check baseline hydrogen and methane levels.

A baseline hydrogen level greater than 16 ppm is considered high, which may be a sign of hydrogen-dominant SIBO, but could also be a sign of improper test prep (59, 65).

A baseline methane level greater than 10 ppm is suggestive of methane-dominant SIBO (42).

The next step is to look at the pattern of hydrogen and methane levels over the two or three hour breath collection period.

When hydrogen levels rise from baseline by more than 20 ppm within 90 minutes, this is typically considered a positive test result (42).

If methane levels are greater than or equal to 10 ppm at any time, including at baseline, it is considered a positive test result (42).

However, it should be noted that interpretation of methane levels is not very well studied and consensus is lacking (42).

Sometimes, hydrogen and methane levels remain low or nonexistent throughout the duration of the test, but it’s unclear why this happens in some people.

If this occurs in someone who displays SIBO-like symptoms, they may have an overgrowth of bacteria that convert hydrogen to hydrogen sulfide, which is not yet detectable on commercially-available breath tests (66).

Sample SIBO Test Results

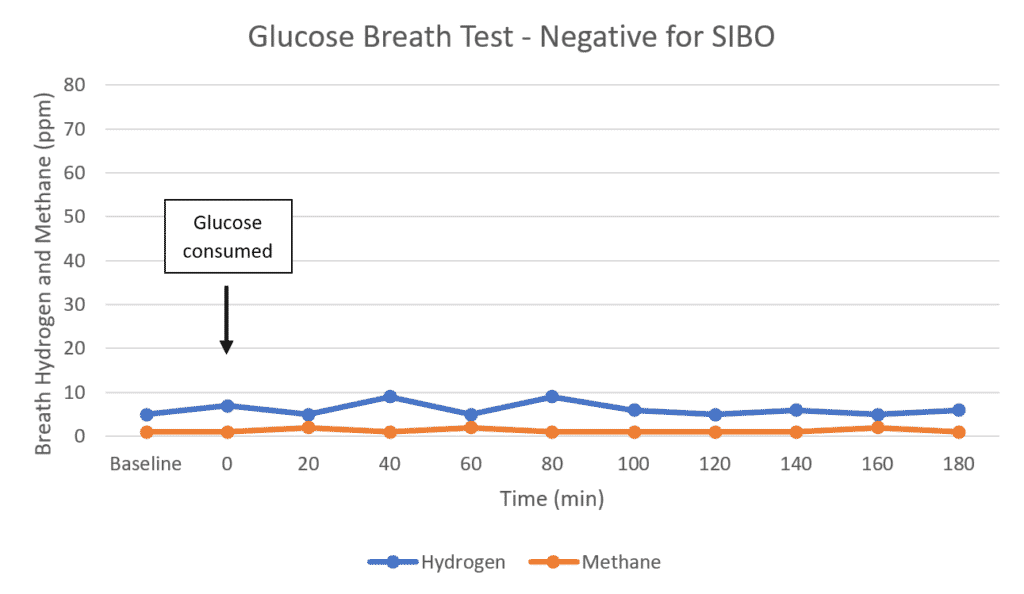

1) Glucose Breath Test: Possible Negative for SIBO

If someone without SIBO takes a glucose breath test, it should look like this (59, 67):

As you can see, hydrogen does not increase more than <20 ppm after the glucose is consumed, which usually means there is no bacterial overgrowth in the proximal small intestine (47).

However, if the person has symptoms (especially diarrhea and rotten egg smelling gas), they may have an overgrowth of hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria that is not detectable on current breath tests.

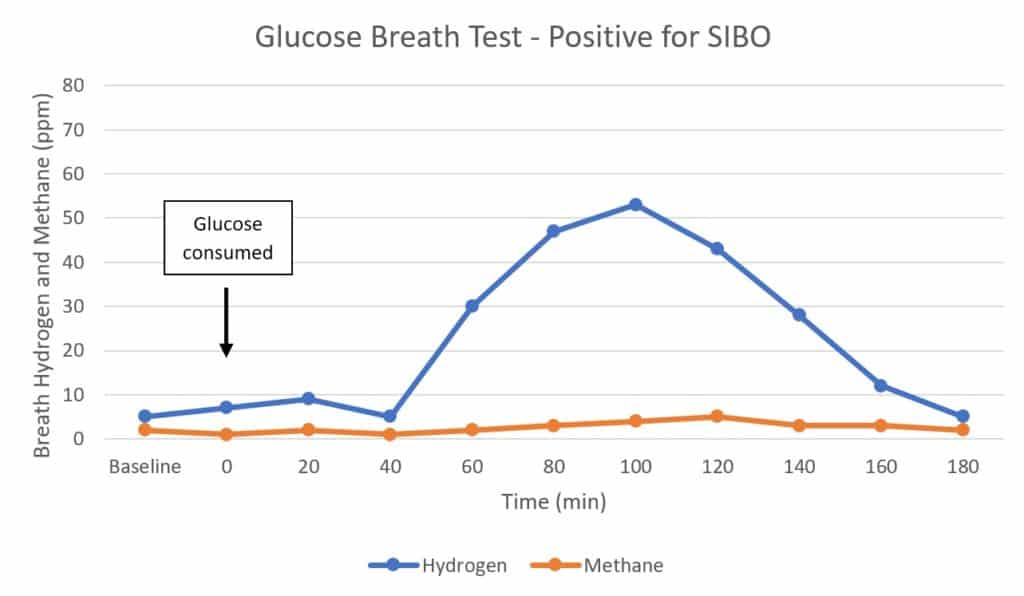

2) Glucose Breath Test: Positive for SIBO

If someone with proximal SIBO takes a glucose breath test, it might look similar to this (59):

Here, you can see that hydrogen increases to form a single peak after the glucose is ingested, showing that bacteria in the small intestine are likely metabolizing it (4, 47, 67).

Because the rise in hydrogen is greater than 20 ppm within the first 90 minutes, this is considered a positive test result (42).

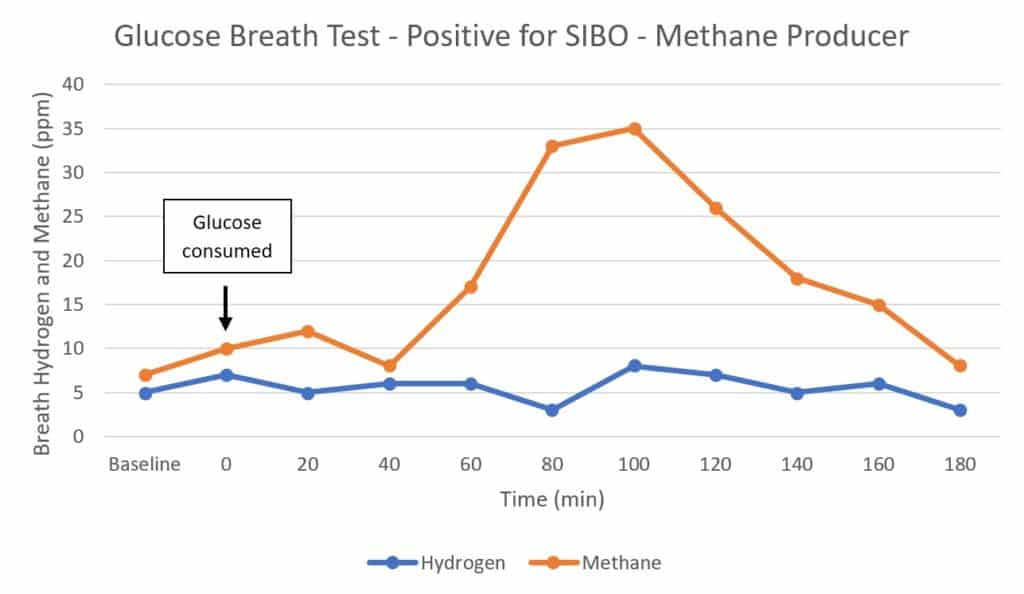

However, if someone is a methane-producer, a positive result might look like this instead (67):

You see methane levels greater than 10 ppm throughout the test, so this is considered a positive result as well (42).

Note that methane production reduces hydrogen levels in the gut, so low hydrogen levels on a methane-positive test does not exclude the possibility of hydrogen-producing bacteria in the small intestine.

No firm guidelines exist for the interpretation of methane levels, so most practitioners follow the generic recommendation that anything above 10 ppm is positive.

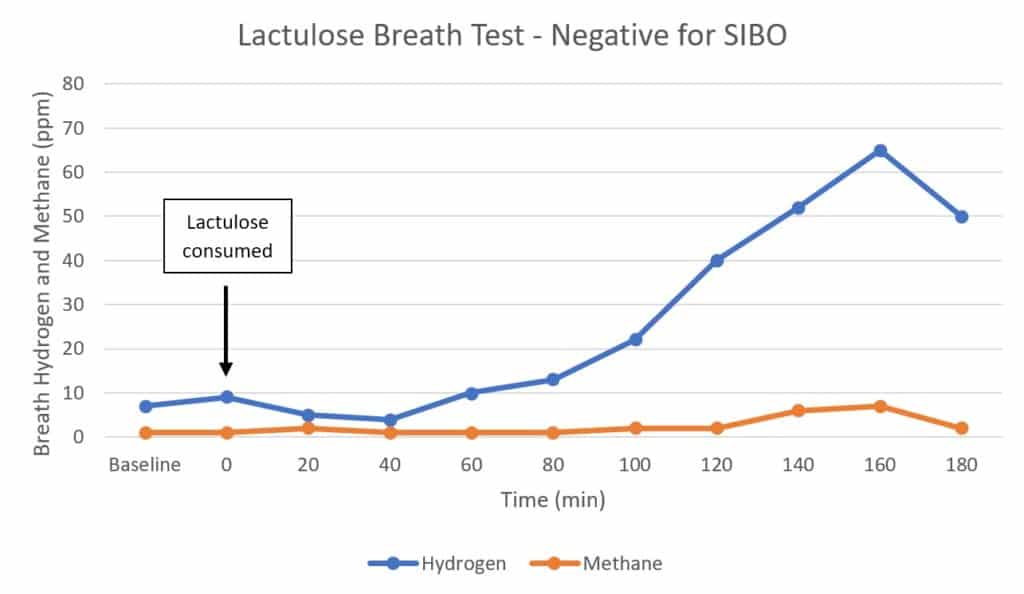

3) Lactulose Breath Test: Negative for SIBO

If someone without SIBO takes a lactulose breath test, it should look like this (68):

Because this person’s gut bacteria are residing where they should (in the colon), you only see an increase in hydrogen once, when the lactulose reaches the colon and is metabolized.

4) Lactulose Breath Test: Positive for SIBO

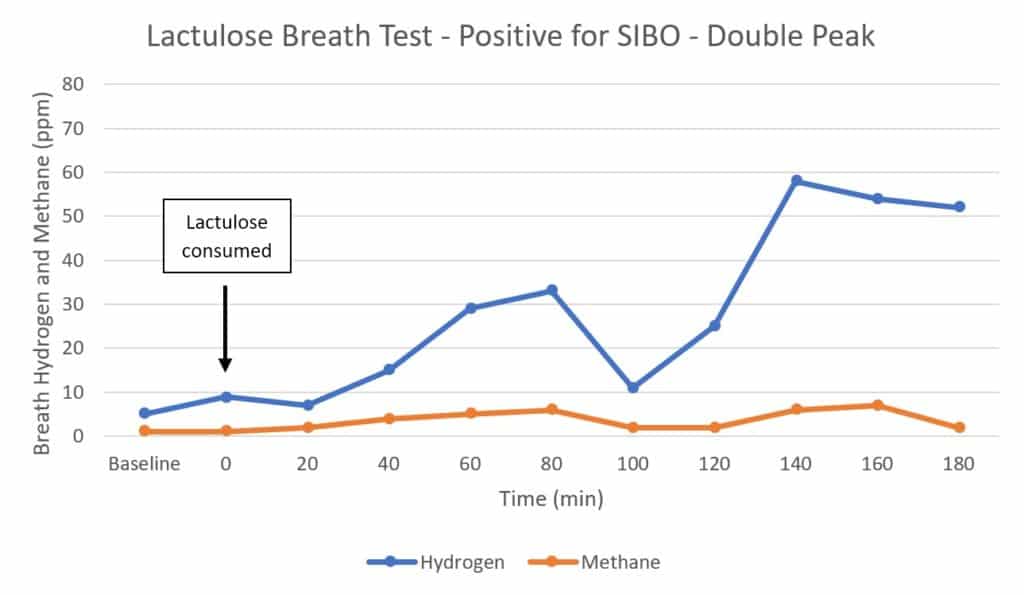

If someone with SIBO takes a lactulose breath test, it might look a little like this (45, 68):

In this case, you see two peaks: one when the lactulose reaches the small intestine and begins to be metabolized by bacteria there, and another when the remaining lactulose reaches the large intestine and is metabolized by colonic bacteria (4).

The rise in hydrogen is greater than 20 ppm within the first 90 minutes, so this is considered a positive test result (42).

However, often a positive SIBO lactulose breath test won’t have a double-peak and will look like this instead (68):

Here, you can see that lactulose quickly begins to be metabolized by bacteria in the small intestine and hydrogen levels continue to rise throughout the test.

In the past, many experts agreed that two peaks were required for a lactulose breath test to be positive for SIBO (42).

However, this single peak presentation is actually more common, and newer recommendations suggest that two peaks are no longer required for the diagnosis of SIBO (42, 68).

Issues with SIBO Breath Testing

Although breath testing is the current preferred diagnostic tool for SIBO, there are several factors that may alter test results.

Fortunately, many of these can be minimized by following a few simple guidelines to prepare for the test.

1. Antibiotic Interference

Antibiotics can interfere with breath testing by killing bacteria and therefore depressing hydrogen and methane production (69).

Some antibiotics are more effective at killing gut bacteria than others, so the effects on hydrogen or methane production will vary (70).

Because it’s still unclear exactly to what degree antibiotics affect breath test results, it’s best to avoid them entirely before taking the test (42, 71).

Antibiotics are often used to treat SIBO, so sometimes a breath test is performed again immediately after finishing treatment to confirm that it was successful (42, 70, 71).

To improve test reliability: Wait at least 4 weeks after finishing any antimicrobials (including herbal treatments) before testing for SIBO (4).

2. Laxative Interference

When laxatives or bowel cleanses are used, large numbers of gut bacteria are eliminated through diarrhea (72).

Because there are fewer bacteria in the gut available to produce gas, excretion in the breath is reduced (4).

In fact, breath hydrogen tests have been used in research settings to evaluate the effectiveness of different laxatives used for colonoscopy preparation. Low breath hydrogen test results show that the preparation was adequate (73).

Unfortunately, taking any type of laxative before breath testing may cause a false negative result (4).

Before testing, patients should be asked if they’ve taken any laxatives, including supplements that have a laxative effect, like magnesium oxide.

Sometimes patients don’t realize that they have been given laxatives for a procedure, so it is a good idea to ask if they’ve had a colonoscopy or barium enema recently as well (74, 75).

To improve test reliability: Wait at least 1 week (but preferably 4 weeks) after using any laxatives or other colon-cleansing solutions before breath testing (4, 42). However, this may not be practical for patients with severe constipation or gastroparesis.

3. Prebiotic and Probiotic Effects

Prebiotics and probiotics both have the potential to interfere with breath test results.

Prebiotics are carbohydrates that humans cannot digest, but gut bacteria can. They remain in the gut until they reach the colon, where the bacteria that live there can consume them as food.

Consuming prebiotics (via supplements or food) may promote the growth of any bacteria currently living in the small intestine, increasing gas production and making SIBO symptoms worse.

It is generally advised to avoid prebiotic-rich foods or supplements prior to testing for SIBO (4).

Probiotics, on the other hand, are living bacteria that can be consumed via fermented foods or supplements.

They can alter the composition of gut bacteria, which in turn, may change the amount of hydrogen or methane produced (4).

However, actual scientific studies are inconclusive as to whether probiotics actually alter breath test results (76, 77).

Align probiotic has been shown to increase methane gas levels in some (but not all) healthy people undergoing a lactulose breath test, without causing symptoms (78).

This suggests that the probiotics caused a transient increase in bacteria in the small intestine as they moved through the digestive tract, but did cause a true overgrowth.

To improve test reliability: To be on the safe side, it might be worth discontinuing any prebiotic or probiotic supplements for up to 4 weeks before taking the test, but it’s unclear if this is absolutely necessary (4, 42).

4. Effects of fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs)

As discussed earlier, breath testing depends on the ability of bacteria in the small intestine to ferment a set dose of carbohydrates.

If any other carbohydrates are available for the bacteria to ferment, excess hydrogen will be produced, and the test results won’t be reliable (42).

Fermentable carbohydrates (also known as FODMAPs) include fermentable oligosaccharides (fructans and GOS), disaccharides (lactose), monosaccharides (fructose), and polyols (sugar alcohols) (79).

They can be found in a variety of whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, fruit, vegetables, dairy, and artificial sweeteners (80).

Some practitioners disagree about which foods are acceptable to consume the day before the test, but most recommend following a low-fiber diet with foods such as: (81, 82, 83, 84)

- Baked or broiled chicken or fish

- Eggs

- Plain steamed white rice

- Limited fat and oils (no butter or margarine)

- Salt and pepper (no other herbs or spices)

- Non-flavored black coffee or black tea (no sweeteners of any kind)

- Plain water

Certain testing centers also allow white potatoes and white bread, but these may cause greater hydrogen excretion than plain white rice, so it’s probably best to avoid them (85).

For best results, it’s also recommended to complete an overnight fast from ALL food and drink (except for water) before the test (42).

To improve test reliability: Consume a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates the day before the test. Fast from all food and drink (except for water) 8-12 hours before the test (42).

5. Cigarette smoking interference

Several gases, including hydrogen and methane, are produced during the combustion of tobacco (4).

Increased hydrogen or methane from smoking could interfere with the test and potentially cause a false-positive test result.

It’s not clear how long it takes for hydrogen levels to return to normal after smoking, but one study found that it took only 15 minutes for hydrogen levels to normalize in young, healthy volunteers (86).

However, hydrogen levels may remain high for longer periods of time in individuals who have chronic lung disease, because normal lung function is impaired (87).

To improve test reliability: At the very least, smoking should be avoided for 15 minutes prior to taking a breath test, but avoiding it entirely on the day of the test is better (4, 42).

6. Impact of oral hygiene products

Over 700 species of bacteria have been detected in the oral cavity, many of which produce gases, such as hydrogen, when they ferment sugar from the food we eat (88, 89).

During a breath hydrogen test, these bacteria will produce some hydrogen gas from the glucose or lactulose substrate in the mouth (89)

Mouthwash kills these bacteria and may prevent interfering hydrogen excretion, reducing the risk of a false positive result.

However, some labs ask that you don’t use mouthwash before the test, so it is best to follow their guidelines.

To improve test reliability: Follow the lab instructions to know whether or not to use mouthwash before the test (4).

7. Impact of physical activity

Studies have shown that hydrogen excretion can vary depending on your breathing rate (90).

Hyperventilation (rapid breathing), such as occurs during exercise, leads to decreased hydrogen levels in your breath, which could cause a false negative test result during a breath hydrogen test (91).

To improve test reliability: Do not perform any activity that increases your breathing rate, such as exercise, right before or during the test (4, 42).

Future Directions for SIBO Testing

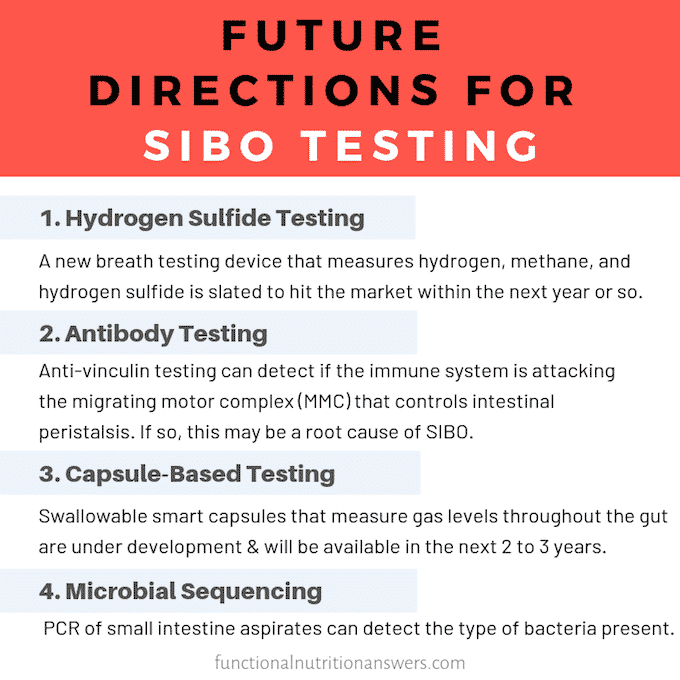

There have been recent advances in SIBO testing methods and exciting developments are on the horizon.

1. Testing for Hydrogen Sulfide SIBO

As mentioned above, a new breath testing device that is capable of measuring hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide is slated to hit the market within the next year or so.

High tech devices used in research studies suggest that hydrogen sulfide levels above 1.2 ppm likely indicate the presence of SIBO (92).

2. Antibody Testing

In some cases, food poisoning may trigger an autoimmune attack on the migrating motor complex (MMC) that messes up gut motility, increasing the risk of SIBO.

Researchers believe this occurs when pathogenic bacteria secrete a toxin known as CDT-B.

CDT-B is very similar in structure to a protein called vinculin, which is involved in coordinating peristalsis waves in the gut.

This similarity can trigger the immune system to accidentally attack vinculin, disrupting the migrating motor complex (the electrical signals that control gut peristalsis between meals) (93, 94).

There are tests available to check if the body is creating antibodies to CDT-B and vinculin. If it is, antimicrobial treatment and a prokinetic are often used to eliminate the infection and restore proper gut motility.

Antibody testing can be done through IBS-Smart, Cyrex Array-22, Commonwealth Diagnostics IBSchek, or Vibrant America IBSSure.

However, food poisoning (and a disordered MMC) is just one possible cause of SIBO, so a negative antibody test does not rule out SIBO caused by other factors.

Additionally, a positive test does not guarantee the presence of SIBO, since it is possible for a disordered MMC to trigger IBS without an overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine.

This test is most helpful in determining whether disordered MMC may be a root cause of a person’s SIBO so it can be addressed accordingly, not for diagnosing SIBO itself.

3. Capsule Based Testing

One of the most exciting innovations in the SIBO testing space is the development of a smart capsule that can be swallowed and detect hydrogen levels every 5 minutes as it travels throughout the entire GI tract.

What’s even cooler, is that the data is automatically sent to an app on your phone so you can see what’s happening in real time!

This technology is currently being piloted with promising results and is slated to hit the market in the next 2 to 3 years (95).

4. Microbial Sequencing

Ideally, we would be able to assess both the amount and type of bacteria present in the small intestine.

This can be done by taking a sample of the fluid in the small intestines and performing PCR (polymerase chain reaction) analysis to detect microbes in the gut based on their DNA (96).

This methodology allows us to identify microbes that don’t grow well on a typical growth medium and wouldn’t show up in the “gold standard” aspirate and culture method.

PCR analysis of small intestinal aspirates is not routinely done at the present time, but holds a lot of promise for furthering our understanding of the gut microbiome.

Final Thoughts

Breath tests are currently the simplest, most convenient method for diagnosing SIBO.

Tests that use glucose as a substrate have the highest diagnostic accuracy but may be unable to detect SIBO that occurs in the distal small intestine.

Lactulose, on the other hand, can detect SIBO in any part of the small intestine but has lower diagnostic accuracy and is more prone to false-positive results.

Choosing a test that combines both glucose and lactulose is an excellent way to gain a better understanding of the patient’s clinical picture and can make interpretation easier.

To improve the reliability of breath tests, it’s necessary to follow test preparation guidelines, which includes fasting 8-12 hours prior to the test.

Because of the limitations of breath testing, some practitioners may choose to do a “therapeutic trial,” which involves treating for SIBO even without a positive test result, if the patient has a predisposing condition and is presenting with many of the symptoms.

Navigating this can be tricky, and ultimately, only a physician is qualified to make a definitive diagnosis of SIBO.

Interested in saving this article? Click here to get a PDF copy delivered to your inbox.

Amy is a registered dietitian nutritionist and experienced nutrition editor. She received her Masters in Nutrition Diagnostics from Cox College and her Bachelors in Dietetics from Missouri State University. She currently works as a nutrition editor for Healthline and Greatist. Her passion is finding ways to communicate nutrition research in an interesting and easy-to-understand way.

This post was well thought out and had great info! I loved the breakdown and that it is evidence-based. I will be sharing this 🙂

Great evidence-based article on a topic that I’m sure many are curious about!

Such great info- thank you! Didn’t even think about how antibiotics could interfere!

Such a great article and thorough explanation of SIBO breath testing, including pros and cons of each test. I didn’t know about the capsule that’s being developed-can’t wait!

very thorough article! Wish it was published back when I was researching SIBO for my own personal needs!

Thank you for taking the time to write this post! Such helpful information for clients.

This was incredibly useful. Thank you for putting so much detail into this!

You have done an amazing job on this post! It’s so informative but easy to follow along. Will definitely be sharing this with a few clients.